Doghole Port: Fort Ross Cove

Fort Ross State Historic Park

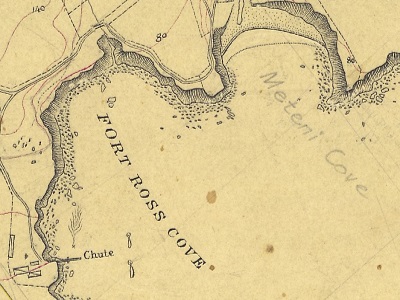

Fort Ross Cove's northern shoreline was the focus of the port's lumber activities. James W. Dixon built the first trough lumber chute there in 1867 and additional trough and wire lumber chutes operated there between 1901 and 1921. Unlike nearly every other doghole port in the area, Fort Ross had a stone wharf that was originally built by William Benitz. Located east of the chute, George W. Call expanded the wharf in the 1870s with a warehouse and derrick to support his shipping operations. Vessels stopped at the Fort Ross Cove facilities to load lumber, stone, hides, produce, and passengers bound for San Francisco and other ports.

Fort Ross has a long and varied history and is now a significant public resource managed by California State Parks (CSP). During the 2016 Doghole Ports Survey, archaeologists conducted land and underwater investigations of the port's northern shoreline and located many features associated with the lumber chute and other shipping operations. The team recorded numerous iron bolts and rings along with rebates in the shore-side rocks to support the lumber chute's legs and support beams. Archaeologists also surveyed the remains of the stone wharf.

Underwater surveys sought to locate evidence of the schooner J. Eppinger which crashed into the wharf in 1901, but failed to find parts of the vessel. Diver surveys further out into the cove targeted the location of the lumber chute ends to search for artifacts. These surveys found a small anchor and several other heavy scrap iron objects that likely served as a permanent moorings to position vessels under the chute end.

Project archaeologists also made monitoring dives on the shipwreck of the Pomona, which sank in the cove in 1908. The Pomona struck a submerged rock south of Fort Ross as it traveled from San Francisco to Eureka. Seeking to prevent significant loss of life the captain steamed into Fort Ross Cove hoping to ground the vessel on its sandy beach. Rather than reaching the beach, the Pomona grounded on a wash rock where it remains today after much historical salvage. The site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is an excellent example of an iron-hulled propeller-driven coastal steamship that carried freight and passengers.

-- Deborah Marx, Maritime Archaeologist, Maritime Heritage Program, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

The chute and stacked lumber on the bluff at Fort Ross Cove in 1892.

Credit: San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, Mercedes Pearce Staff Collection, E11.19,777pl (SAFR 21374)

U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey T-sheet from 1876 shows a lumber chute at Fort Ross Cove.

Credit: NOAA's Historical Map & Chart Collection

This diorama in the Fort Ross State Historical Park visitor center conveys the engineering complexity of a trough chute.

Credit: California State Parks

NOAA ONMS Maritime Heritage Program Director Dr. James P. Delgado and CSP archaeologist Airielle Cathers record an iron pin with a GPS receiver and tape measure.

Credit: NOAA ONMS and California State Parks

CSP archaeologist Scott Green measures a square notch cut into a boulder which held one of the lumber chute's support legs.

Credit: NOAA ONMS and California State Parks

The lumber chutes were secured to shore with cables tied into iron pins and eye bolts.

Credit: NOAA ONMS and California State Parks

The survey included the nearshore rocks where the main lumber chute legs were often positioned.

Credit: NOAA ONMS and California State Parks

NOAA ONMS maritime archaeologist Deborah Marx examines the steamship Pomona's remains now home to abalone, sea urchins and a variety of fishes.

Credit: NOAA ONMS and California State Parks

The project team documented underwater remains of the Redwood coast lumber industry including this anchor in Fort Ross Cove.

Credit: NOAA ONMS and California State Parks